The final year: visualizing end of life

In the year before you die — especially if you are very sick — your life may be shaped by medical procedures.

Over the course of your final year, you might interact with healthcare providers in different contexts: regular appointments with specialists, hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility stays, emergency department visits, end stage renal disease (ESRD) treatments, and others. As visualized by Nick Stepro in The Final Year, sometimes these end of life interactions form a difficult and painful path, and sometimes, by fortune or by planning, less so.

Your final year — a journey through the healthcare system

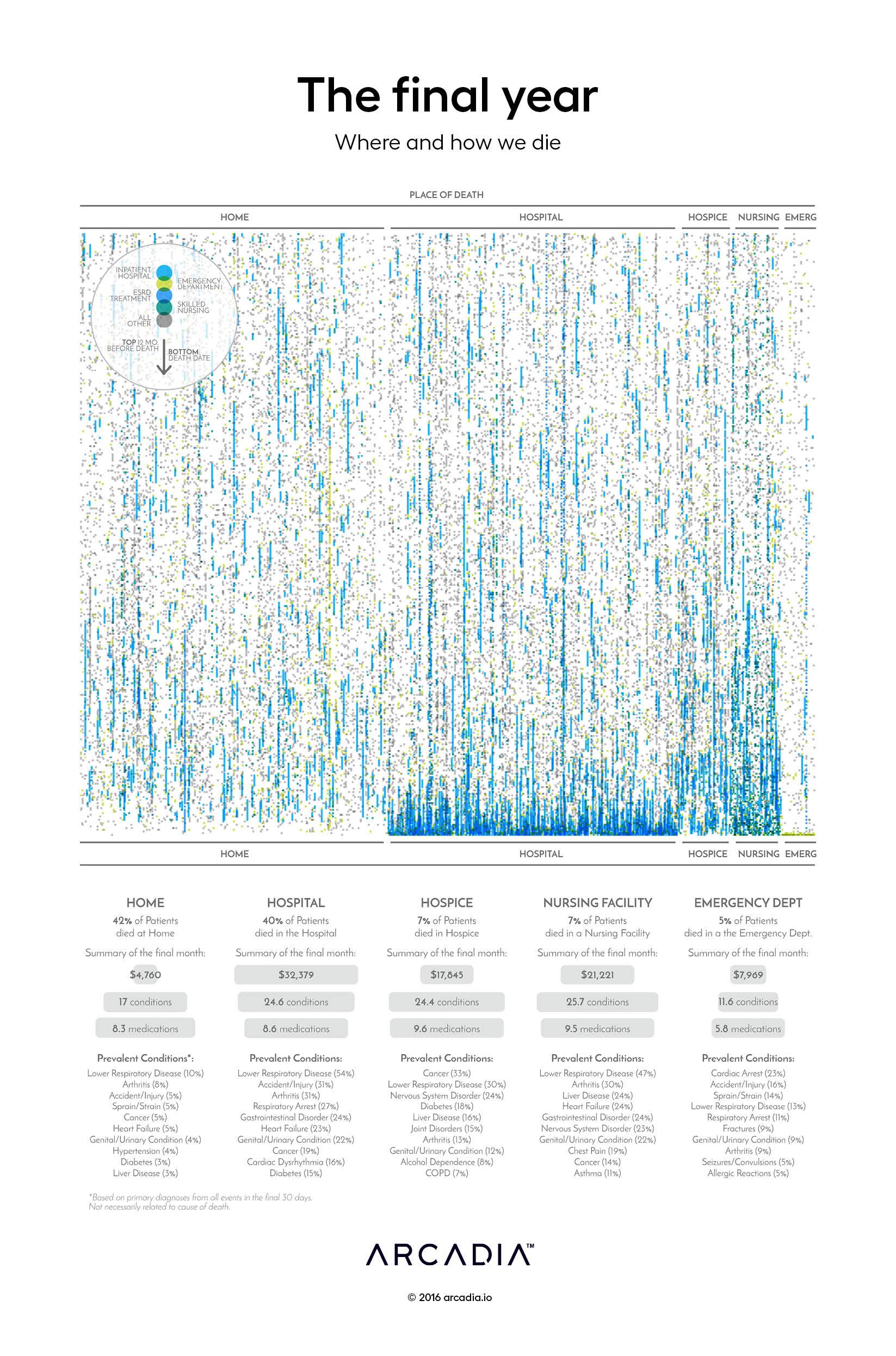

The Final Year depicts the healthcare experience during the final year of life for 2,398 patients who died during a five year span. Each patient is represented by a single column; the columns are grouped along the horizontal axis by the estimated environment in which the patient died.

The columns are composed of a series of points representing interaction with the healthcare system during each patient’s last year of life, as identified through clinical and claims records, and colored by the place of service for the event.

At first glance, this may seem like an abstract pattern. But run down a column, and the points become not just a staccato rhythm of blue and green and grey, but a manifestation of a very human experience at end of life.

- Did this person die from trauma in the emergency department — bright lights, people shouting, searing pain?

- Could this patient spend her final weeks at home with family?

- Was this person in the hospital, confused and scared, with unfamiliar faces doing painful things?

Each of these colored points represents a very real medical experience, and for many patients those interactions come one after another after another. At some point, perhaps, a more fortunate patient may have had the opportunity to explicitly discuss end of life care with his or her primary care physician.

End of life care — an uncomfortable conversation

Conversations about end of life care are challenging for physicians, patients, and their families. Perhaps even thinking about this in an abstract way makes you uncomfortable — imagine preparing to have this discussion with your patient waiting in the exam room, or with a family waiting outside the ICU. What would you say? Physicians need training to be able to initiate this type of end-of-life care conversation, and to handle the spectrum of emotions it may initially elicit. (And, perhaps of equal importance, physicians also need to find enough time in often-overbooked schedules to have this kind of dialogue.)

Patients and their families, meanwhile, must wrestle with these intense emotions while also trying to make decisions about complex medical procedures with no clear answers. An elderly man hits his head, so his son races him to the emergency department. The man is bleeding in his brain, but surgery will likely kill him or leave him in very poor shape. What decision should the son make, and how can he avoid feeling guilty? For laypeople, these can be challenging, difficult decisions to understand and make under duress. Some decisions are big, some small: Should an experimental medication be tried? Should a DNR order be in place? Can this medication be administered at home?

In trying to understand and make each of these decisions, one after another, it is easy to lose sight of the big picture — how do we spend our final year? How do we want to die?

How — or where — do we want to die?

As it turns out, the question “how do we want to die” might be reframed “where do we want to die” — location matters.

The most obvious difference experienced by the patients studied here is the difference in their final month across the different places of death. Most immediately apparent is that those who die at home or hospice — in this analysis, some of those who died at hospice may be assigned to home due to lack of activity — appear to have a tapering of healthcare activity toward the end, whereas those whose end-of-life occurs in the hospital tend to spend their last days and weeks there, as evidenced by the cluster of blue.

In many cases, patients who spent their final days at home had previous hospitalizations — perhaps death came unexpectedly, or perhaps there was a deliberate decision to avoid what Dr. Ken Murray, MD calls “futile care” in his widely-republished essay on how doctors choose to die differently.

The cost of death — human and financial

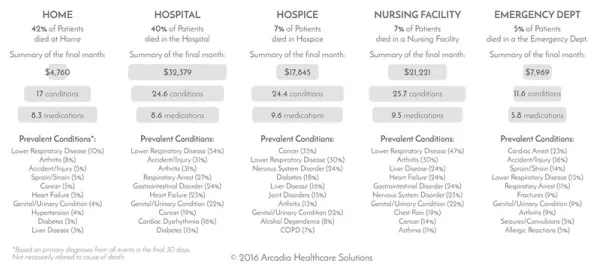

While patient quality of life is of course paramount, The Final Year also explores the average costs, conditions, and medications associated with each place of death.

In the introduction to their paper on the relationships between health care costs, end-of-life conversations, and intensive interventions, Zhang et al note that approximately 30% of Medicare costs are attributed to the 5% of beneficiaries who die each year, with 78% of those costs stemming from life-sustaining acute care during the final thirty days of life. Given that patients may not fully understand their options for end of life care, especially when that care may be futile, and given the costs associated with acute care, healthcare systems — especially those engaged in value-based care — may want to prioritize patient access to palliative and hospice care programs.

Beyond cost management, end of life conversations offer a real opportunity to improve the quality of life for patients — empowering us to choose where — and how — we die.