What happened during the 2022 RSV surge?

Looking back at fall’s respiratory syncytial virus case numbers and the data that led to overwhelmed hospitals.

In the fall of 2022, the tripledemic dominated headlines. COVID had turned the healthcare industry on its head when it emerged a couple of years before, and the flu has always taken a heavy toll in winter months. But in this case, the third ingredient made for an especially difficult combo.

That third curveball was RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), a common illness that usually presents like a cold. The people most at-risk are very young children, the elderly, and the immunocompromised. According to the University of Chicago, it’s a leading cause of hospitalization for infants even in a “normal” year, and almost all children have been infected at least once by age two.

Here, Arcadia’s Executive Director of Customer Insights Jake Hochberg uses clinical data to tackle some of the questions left in the wake of RSV mania. Why was 2022 in particular so terrible? What caused hospitals to suddenly experience a shortage of beds? And were last year’s numbers really so aberrant from a normal season?

Read on to learn more about what the Customer Insights team excavated from a few months of analysis, and what questions healthcare experts will need to answer before they’re equipped for a smoother response.

More RSV cases + less time = chaos

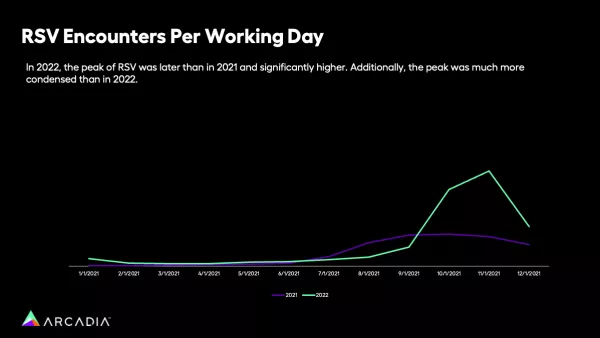

According to the data Arcadia pulled, what made 2022’s RSV cases so difficult was a combination of more patients and less time to prepare or regroup. Those headlines about bed shortages and overwhelmed hospitals came in the wake of a steep spike, when previous years had dealt a more gradual blow.

“One of the biggest talking points in the data pull was that, RSV in 2022 case volume was two times higher than it was in 2021, so it went up a lot,” Hochberg says. “But the actual peak period of RSV was 3.3 times higher in 2022 then 2021. This condensed period is what really strapped the healthcare system.”

In other words, yes, there were more diagnoses of RSV, but that alone wasn’t enough to create headline-making chaos. The factor that made things most dire was how condensed these cases were. Where, in previous years, cases were spread evenly across several months, the chart above shows how 2021’s cases spanned September-November fairly evenly. In 2022, that changed, and a whopping 67% of cases took place in November alone. This fast and furious pace meant that hospitals had a sudden influx of very sick patients, and no time to make special preparations.

How timing escalated RSV’s impact

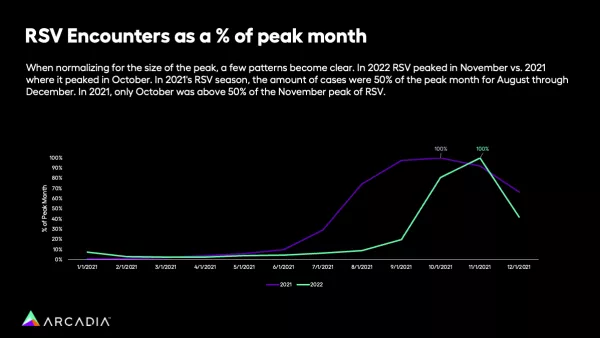

To understand the difference in timing, Hochberg compared the relative percentage of diagnoses by month, irrespective of volume. By removing the actual number of cases, it’s easier to see the difference in concentration — the way 2021’s cases slowly curve over several months, where 2022’s skyrocket and then plummet back down.

“If you look at 2021, in September, the month before the biggest peak, RSV was at about 90% of where it ended up in October. Even in August, it was at about 70% of where it was going to ultimately be in October, so it crested much more slowly,” Hochberg explains.

The shift to 2022 was abrupt.

“If we look at 2022, in October RSV was like 80% of that peak. Even two months earlier, in September, it was at only about 20% of where it ended up. And even in December, it was below 50% of where it was,” he says. “It just really highlights the speed and aggression of this year's peak.”

State and regional trends for RSV in 2022

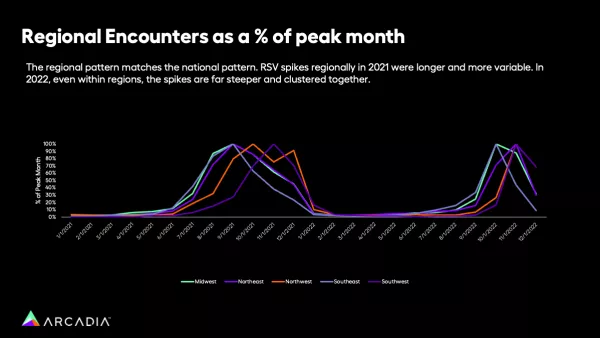

When Hochberg and his team delved even deeper into the past two years’ clinical data, they were able to look at how things played out region by region.

“In 2021, across these five different regions, there's actually three entirely different time periods that it peaked,” Hochberg explains. “So some peaked in August, some peaked in October, some peaked in November. And even within the health systems, there was a much bigger spread of when these peaks were happening.”

In other words, in 2021, a hospital in Kentucky might have had their worst week for RSV in September, whereas New Mexico fared worst a couple of months later in November. In 2022, that changed.

“In 2022, all of a sudden, every region we saw peaked in either October or November, and every region had that crazy escalation pattern where it jumps from the month before to the peak month in a much narrower time window,” Hochberg says.

Within regions, RSV hit its peak suddenly and quickly, and across regions, that happened at the same time.

The questions we’re still asking about RSV

There’s a lot analysts can do with detailed clinical data, but learning the full story will also take time. As insurance claims data rolls in, it'll add additional context to what we know now, especially around the severity of cases. Potentially, this deeper dive will help healthcare organizations better prepare themselves with demographic knowledge for the next winter.

Preparing for major, unexpected crises that come on suddenly isn’t an easy task, no matter how much data you’re equipped with. For now, Hochberg advises watching the curve as diagnoses roll in.

“My view is, in the future, if the pace seems to be escalating at a faster rate, that indicates that you're going to probably hit a peak and have some hospital volume issues,” he says. It doesn’t ensure a cushion of months (or even weeks) to brace for impact, but in the meantime, organizations can have a plan in place for a sudden influx like 2022’s.

Data lets healthcare organizations take the pulse of their populations, whether it’s a tripledemic or a mild flu season. Tune into our latest webinar on SDoH strategies to learn how you can pair insights and action to keep communities healthy.